Do it Together: Maker Culture and Turkey

Published in ATÖLYE Insights · 12 min read · August 21, 2017

Exploring the geographical variants of the Maker culture

Author: engin ayaz, Co-founder & Head of Design, Editor: Emre Erbirer

At ATÖLYE, we work closely with aesthetic and technical constructs alongside socio-cultural precedents and contexts. As strategic designers, we remain pragmatic in our approach and only dig deep enough to conduct 'design research,' which implies a more generalist, qualitative and 'sensing' mode of understanding the world. On the other side, we are aware that there is certainly a vast world of academic social science research that digs deeper, and explores political, economic and social relationships at a much more quantitative, evidence-based manner.

Carrying this rather pragmatic and strategic lens, we'd like to articulate our perception regarding Maker Culture and Turkey, at a level that remains closer to intuition and reasoning than in-depth field analysis.

In this context, we argue that the future of the maker movement in Turkey could be grounded in collective production rather than individual production, considering some patterns of the prominent culture of this land. In a scenario in which personal and mutual trust is invigorated, unique projects which could not even be dreamed of in the US probably may come to life. However, to achieve this, we must first examine the external, and then the internal situations. Hopefully, this article can be a guide throughout this journey.

We are aware that in a Baudrillardian sense, this map of the territory will inevitably be limited, but hopefully, it spurs a conversation that enables a deeper discourse.

ROOTS

Though 'making', 'producing' and 'becoming a craftsman' date way back in history, the word 'maker' is used to determine a subculture that was born in the contemporary US. The factors creating this subculture should be mapped well so that the goals and the future of similar international structures can become clear.

The emergence of the maker movement in the US can be attached to four different factors; urban planning, value of labor, individual society, and a culture of experimentation. The fact that these factors span across spatial, economic and cultural axes explain how the maker movement arrived to where it is today.

Urban Planning

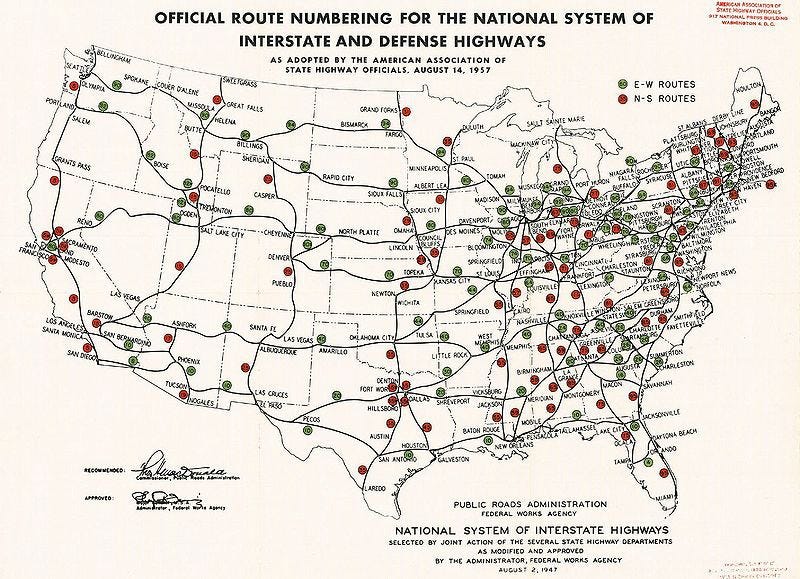

In sprawling America, the highway network started as an Interstate project initiated by Eisenhower in 1956, where the initiation brought the 'suburban' urban development model with it (UVM, 2011).

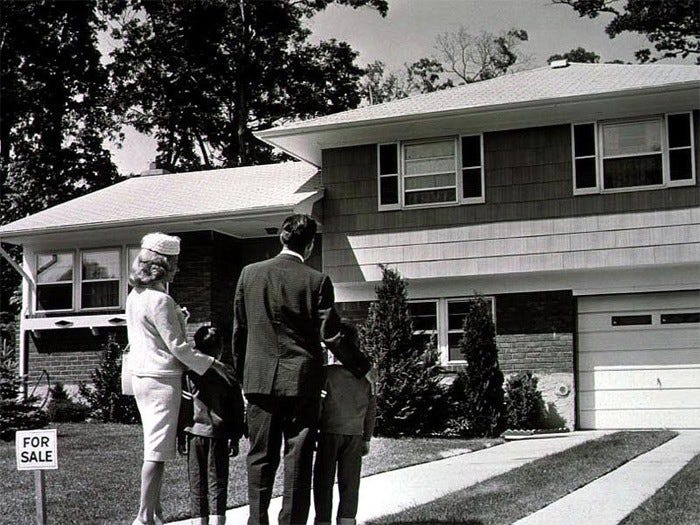

Families living in spacey houses in rural areas outside of the city became part of a narrative situated away from public services. Cars, the inseparable part of this system, were situated in the garages of these new dwellings as "separate houses". As a result, the car held an uncompromisable place in the relationship that the entire family established with the external world and hence needed a separate closed space. The condition of remaining distant from services caused these large garages to develop secondary functions.

Among these functions was the storage of tools that would normally be used by carpenters, plumbers, electricians, gardeners, which were now used by the inhabitants of the house instead.

Families that lived in such distant locations and owned these secondary spaces quickly increased and became the natural pioneers of the 'do it yourself' movement (Smith, 2014). Thereby, a number of following generations in America were thought to learn such skillsets. In fact, the same garages provided flexible spaces that have been instrumental in turning hobby-based internet ventures into entrepreneurial initiatives, which "leapt from atoms to bits" through the internet revolution.

The Value of Labor

In America, the cost of hiring someone to fulfill manual labor jobs was always high for a middle-class family. As the hourly charge for plumbers and electricians reached $100, handiwork required physical labor and expertise became a type of work that people took upon themselves, through self-improvement and self-empowerment. Therefore, the 'do it yourself' culture was not merely born out of long intercity distances, or a romantic ideal of self-realization, but also of economic reasons.

Experimentality

Today's America started out as a big collective experiment. Innovation and risk-taking were embedded in the cultural DNA of the continent that was transformed through migration. Each individual in the States had learned, experimented, and made a place for himself/herself within society. Instead of the traditions brought on with the feudal regime, meritocracy formed the economic foundation. Tolerating mistakes and regenerating itself rapidly, this new structure emphasized and championed game-changing attitudes and persistent experimentation. It is not surprising that in today's world, innovation, a term that is politically agnostic and neutral, has originated in this land.

Individualistic Society

The individualism of American society is a very important cultural factor, unequivocally. The history of this situation can also be explained through economic reasons. The white-collar employees, who worked nine-to-five and had limited spare time, were able to make time for themselves by purchasing, rather than producing resources. At the same time, the isolated individuals created secondary support mechanisms for amusement. In addition, the "each individual is unique" myth was popularized by marketing prodigies in order to further encourage consumption. Thus 'self-realization' became increasingly important. In this context, the sharing culture which has come through with the internet revolution became revolutionary for "DIY" groups. Relatively small groups became part of a large cybernetics network. The feedbacks which they received became sources that directly fed into a set of personal values.

ONE BRANCH: ANATOLIA

Looking at Turkey's history and geography, it is certainly impossible to discuss a single immutable culture. Anatolian civilizations undoubtedly contain distinct cases and situations. On the other hand, we can consider mainstream social approaches and factors, especially those that have been formed in the last thirty years. It will be more meaningful to read and discuss the observations of a 'dominant culture' as explained below with the realization that there surely are exceptions.

When we look at the dominant culture in these lands, we are faced with a different historical reality than that of America. The absence of a space between rural and urban settings in a spatial sense, the cheapness of labor in economic terms, and the collectivist structure of the society in a sociocultural sense all provide a contrasting subtext with the American culture.

Lack of the Suburb Model

In our country's urbanization history, the 'suburb' model that remains in between village and city life did not gain ground due to various reasons. Based mostly on an agricultural society, swiftly urbanizing and growing "parasitic" slums in confined spaces and the crowded blocks of flats brought quite a different life to the middle class as compared to their counterparts in America. The population density of cities never gave rise to the evolution of the same 'garages in that of America. These type of structures were only used by upper-middle class and upper class citizens, with the sole purpose of providing space for cars. In compact and limited spaces and distances, it was not a meaningful demand to maintain the tools necessary in a 'do it yourself' culture at home.

In the rural area, a compulsive 'making' approach always existed; however, instead of individual efforts, a mutual approach defined as 'imece' (collective work) became prominent.

The constraint of resources and commonness of required skills caused these small communities to look at making and producing quite differently than in America. In the meantime, the adaptation of the this culture within the city was simply impossible. The lack of trust for anyone except people from the same region brought about the ending of the collective work culture.

Cheap Labor

In comparison to America, in our country with a high urbanization rate, having someone else undertake labor works was easy and cheap due to the rise of the free market economy after the Turkish coup d'état in 1980. This condition that arose in relation to the society's economic past became reflected within the language, as 'traineeship' begun to be perceived as vocational path for a separate class specifically after 1980. Thereby, labor became cheaper from an economic and perceptual standpoint. Hiring other people to do one's own work became more economical.

Lack of an Experimenting Culture

It may be said that mainstream culture became more conservative in this region due to patriarchal roots, a hierarchical structure, centralist governance and common myths within the religion-army-citizens triangle. The questioning of the past and the resistance to change it became its main building stones. A bourgeoisie created by the government opened the way to an enterprising culture, expecting assent and support. Unfortunately, this approach disabled grassroots movement from happening. The strict communication phrase 'do as you're told' as dictated by parents, the reprimands of teachers, the multiple-choice and close ended questions, moved us away from experimentation and scepticism. This appeared as a factor standing in the way of the maker culture, causing the proactive and experimental nature embedded within the culture to be limited to exceptions.

Collectivism

Relatives, friendships and the bearable heaviness of spending time together left less time to discover hobbies and go on journeys of personal development. While this societal structure may be the portion that is hardest to examine, it includes a number of premises regarding the essence of the culture.

In the dominant culture, independent living was not a cause of celebration but was rather labelled as; 'causing controversy', 'outcasting', 'going against norms'. Thereby, 'havving a place in society' always mattered more than the prospect of self-realization, unlike in America. In this context, individuals chose to play a part in the society as mere actors, rather than seeking companionship over social settings like those in America.

PROPOSITION: TRANSPOSE & DO-IT-TOGETHER

In Math, transpose is a term that is used to adapt a matrix function to another topology. Hereby, we can discuss the need adapting the maker culture not by "'cutting and pasting' but through transforming it. Afterall, adapting requires seeking many similar elements. However in this case, we need to extract the core and to place into a completely different paradigm.

Throughout this process, understanding the values that create the essence of the maker culture is as important as understanding the geographical, economical and cultural factors that constitute it. Hereby, we can discuss three such factors:

Productivity

Maker culture is an idea formed during the Industrial Revolution, a time in which individuals started to move forward from being consumers to producers. Thereby, the reasons that encourage the individual to produce should be locally discovered and supported.

Specificity

Maker culture is established upon locality and specificity. It emphasizes that the best problem is the individual's own. Hence the best customer is the individual himself/herself. In today's world, there are a million markets for one hundred people, rather than a hundred markets for a million people. In any case, the internet supplies the whole system and makes the stream easier.

(Self-)Confidence

The maker culture emphasises making mistakes, sharing and collaboration. Every effort made with the intent of improving an individual's social security and self-confidence helps the transfiguration of this culture.

OPPORTUNITIES

When we look at this situation in regards to the Turkish culture, we can actually observe more opportunities than limitations:

-With the intent of inducing productiveness, this culture can reach more people through a promotion of productivity on social media and through events. In cities encumbered with shopping malls and diners, it is possible to create new breathing spaces for production. It is possible to foresee that these spaces will fill up over time, because producing, awakens a very primary emotion of 'I exist by making', as stated by Richard Sennett.

-Specificity can be solved by identifying the problem accurately. Because the problems in this country touch upon far more interesting fundamental issues (education, health, transportation, communication), they may lead to the formation of remarkably interesting projects. These projects may referberate in countries such as Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, South America, in different ways than in America.

Spaces which instill trust and self-confidence may be designed. Ultimately, the social dilemma that we are in may be defined as resulting from our existential search for production and collective presence, while at the same time failing to work together on the account of being untrusting towards each other. This is such a fundamental issue that it can only be interfered with through micro-scaled adjustments. These interferences may consist of both temporary and permanent spaces:

Temporary spaces: Annual events like the Maker Faire matter because they define and gather communities. At a time when retaining concentration is challenging, working efficiently with minimal time consumption will motivate all of the participants and will boost the culture of collective work.

The fact that necessary expenses are only limited to a period of time minimizes risks in all aspects. Both the individual's ability to produce independently and the feedbacks that he/she receives will promote self-confidence. On the other hand, production with collective efforts with no regards to money or economical personal interest will awaken mutual trust. The aim should be to extend the geographical boundaries and to increase the frequency of this type of events as much as possible.

Permanent spaces: In this category, makerlabs, makerspaces, fablabs, hackerspaces, and collaborative workspaces on different scales that serve different professions pave the way for small communities to build qualitative trust and self-confidence. Even though all of these spaces have cultural nuances, their contribution to the localization of maker culture is undeniable. All activities such as weekly feedback meetings, brainstorming sessions, demo days for presenting prototypes and hackathons may enable these permanent places to reach the masses and to spread other derivatives increasingly. This type of quality sharing may constitute the essence of the maker movement in Turkey.

When all of these topics are evaluated, leading the consumerist masses within collectivist societies towards the culture of making that exists in Anatolia and focusing on local and 'real' problems, we would be able to ignite a different style of production. Therefore, instead of focusing on bringing the previously found maker movement here, we should try to convert it and adapt it to this unique setting.

Perhaps, the prominent idea in Turkey will gear towards 'do it together' (or DIT), rather than 'do it yourself' (or DIY). This may even be defined as a new urban collective ("imece") culture.

Why shouldn't we utilize this type of transformed maker movement to become a catalyst for us, as well as other collectivist societies with a similar structure?

—

This article was originally published in Manifold. Special thanks to Aylin Durmaz and Dr. Karabekir Akkoyunlu for their contributions.