Deceleration: In Praise of Slowness and Trust

Published in ATÖLYE Insights · 4 min read · October 10, 2017

Why long-term thinking is the missing ingredient for start-ups

Authors: engin ayaz, Co-founder & Head of Design, Bala Gürcan, Communications Assistant, Editor: Emre Erbirer

In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore famously made a visionary prediction: the number of transistors per square inch would double approximately every 2 years (The Economist, 2016). This meant that computers and all related technologies would accelerate in an exponential pace. Moore was spot on, but what he did not predict was that this cult of speed would not only make our computers faster but create systemic ripple effects across our whole life. On a global scale, we are struggling with a diminishing attention span and an inability for thoughtful reflection, as technology becomes a forcing-function for "getting things done."

This approach leads to a restless culture that prevails throughout all stages of the entrepreneurial quest. Entrepreneurs have come to rely on the 'spray and pray' venture capital funding system, where it is mutually understood that most startups would fail, and yet it is still of common practice to invest in many startups with a low overall success rate. Furthermore, this aspiration of speed has resulted in the demand for "spark", "excel" and "fast works" incubator and accelerator programs, which claim to provide the necessary growth to large numbers of new ventures in durations as short as three months or up to six months.

It is not only the duration of these programs that is shrinking but also the time it takes to raise funding. Whereas in the past, raising a seed round would take months of hard work, today some rounds get raised in mere days (First Round, 2015). Similarly, the duration between seed round and Series A has also diminished, with companies advancing to the next stage in 6 months or less. (First Round, 2015). As the CEO of a company which has failed to meet the super-fast change of demands at this mid-stage once stated; "It was like graduating from elementary school straight into college" (Fortune, 2015)

This pace is all good, but are we collectively aware of what we are willing to give up for the sake of speed?

Consequences

It seems that speed has consequences both on a functional and cultural front.

Functionally, speed implies that failure is more likely to happen, as it either implies less time to think or less time to prototype and test. This tradeoff is already celebrated with the "fail fast" or "do or die" mantras, yet can we really afford to fail in all types of projects? What if the project is just too large in scale, or too irreversible in its impact? Or from another angle, is it really acceptable that only %5–10 success rate among seed round startups is the only financially viable model? Does the world really need more and more unicorns, or perhaps even more solid, reasonably scalable and resilient businesses?

We believe that aside from traditional success measures, culturally, speed comes at the cost of diminished trust on various levels. Think failed startups due to a lack of strong healthy communication among founders, team, investors, service providers and customers. Elsewhere, we are seeing that Uber's new CEO has a remit of fixing the image of the company, and trying to build trust again with slow, careful steps (The Verge, 2017). Even on an interpersonal level, research suggests that most professional crises may end up having a lack of trust at their root (Janessa Lantz for Think Growth).

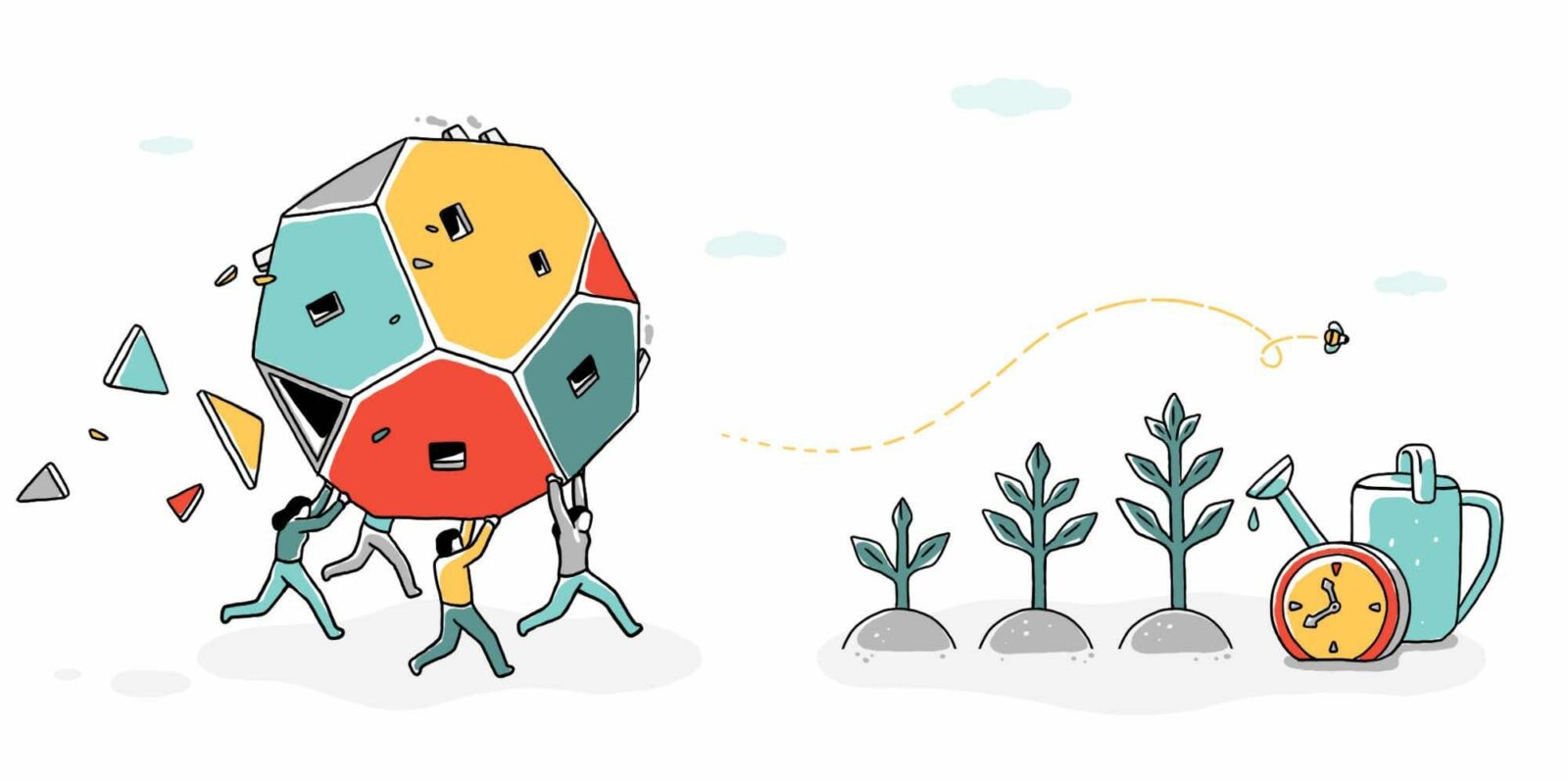

Trust and speed have a negative correlation. Trust between peers takes a long time to cultivate, and yet it is most of the time the missing ingredient in start-ups that are moving at full-speed.

The other end of the speed spectrum consists of slow practices: planning, impact assessment, stakeholder engagement, community building and foresight research, among others. These services sit usually within realms of academia and government, and occasionally within specialist consulting firms. Meanwhile, these activities are clearly at friction with the desired pace of the entrepreneurship world.

"Movers and shakers" and "makers" are clearly needed, but what is it good to change things without proper reflection of the past, and projection of the future?

Zooming out, it is no accident that the words "culture" and "cultivate" have come to derive from the same Latin root of cultural, meaning "growth" (Fast Company, 2015). It is important to keep in mind that building something from scratch is a long and challenging process, as it takes time to build a solid, sustainable, and profitable business and its desired audience. We see a lot of potential in the acts of gardening and farming rather than cattle herding. Invest in the soil, create the right environment, and be patient regarding the outcomes.